Olive DM’d me on Twitter in May 2022: “Boy have I got a story for you.” It was an odd message, out of the blue, from someone I didn’t know. As a researcher of technology and capitalism, I had been studying NFTs “on scene” for about a year, traipsing between some of the bizarre online chatrooms in which electronic assets are hyped.

I had begun to meet artists and posters through making my own collages. Taking a quick peek at Olive’s profile, I saw Milady Maker art everywhere, collaged/edited/memed, along with the absurd style of posting they call “network spirituality.” I knew about Milady because their NFT art stands out so much: the art is bizarre, the tweets quirky. If the average internet user stumbled across one of these tweets, they’d think little of it besides, “That’s weird.” Seen in context or community, though, the social performance is political.

Me and Olive have at least one thing in common: On a place like the internet where everything feels copy-paste, some of us are looking for something else.

So I took a call with Olive. They led me through their story, from that late night in August 2021 with Prelon, to their ghosting of the Second Milady Rave due to “vibes,” opting for a night at home with some NYC artists-turned-Milady folks and a “big bag of ketamine.”

Olive had a lot to say and gave me a crash course on, well… I’m not completely sure. They explained that finding “avant NFTs” on the stale NYC art scene wasn’t about crypto, at least not at first. For them and some other underground NYC artists, it’s something bigger, something called “network spirituality,” a way to use the internet that rejects just about everything your parents might accept about the internet.

First and foremost, this spirituality is “post-authorship,” where everything is a meme, i.e., graphic and textual art is made for repurposing, à la Barbara Kruger and collage, but rapidly, on the network, with no citations and no credit. As Olive put it,

Symbolic signifiers… network spirituality… once fluent, you can feel the network. People have the capacity to develop a sense. It’s a spiritual process where the self is sublimated into the network.

According to Olive, some (including an internet artist and activist named Charlie) conjure something called a “tulpa,” a being that inhabits the body and can then perform on the network. The tulpa is just one of many occult and esoteric references being used by practitioners of this odd way of using web platforms.

Let me back up. Before I tell you Olive’s story—typical of a way of exploring the internet which I think is becoming increasingly common—here’s some context.

There are two narratives about the internet. The most common one circa 2023 looks something like this. In the beginning, the internet was a disparate and purpose-built place. Niche segments of society—academics sharing scientific data, the military communicating battlefield maneuvers—used and developed the internet. As the internet became commercialized, an eclectic assortment of online services arose to, first, meet specialized and business needs, and later, those of the general public.

Fast forward: the dot-com bubble bursts, hastening the consolidation of the internet into a succession of platforms. Before there was Facebook there was Myspace, and before that there was AIM and AOL, and before that GeoCities, and on. Now, what happens on the internet occurs thanks to an increasingly concentrated number of service providers. In this view, the internet is a useful place that is free to use, has more than enough to offer, and is loved by your parents.

There is another story of today’s internet, and it’s probably not one you know. The Internet was developed as part of the U.S. government’s command and control structure in the thick of the Cold War. Since then, the internet has coalesced into a growing number of platforms operated by a shrinking number of tech giants—and tech oligarch-bros. In this narrative, there’s a small cadre of internet users who are fed up with it all, especially social media. They look for and use alternate platforms. Sometimes they build their own. These users are uncomfortable with internet companies like Meta—Facebook’s parent company (and Instagram’s, and WhatsApps’s)—owning, analyzing, and ultimately adapting their services in real-time to increase screen time, monetizing each click and view.

Hence, the internet is a web of contested spaces under strict and constant surveillance—and is best enjoyed when highly memeified.

For one discussion of the tensions and synergies between those who own internet infrastructure, “vectoralists”, and those who create on internet infrastructure, “hackers”, see McKenzie Wark, Hacker’s Manifesto.

Olive’s story asks an important question: What happens when artists, anarchists, and increasingly, just random people making memes on the internet, do things that aren’t anticipated by today’s internet platforms?

Late one night in August 2021, Olive was scrolling, and looking for something. Outside, the latest COVID-19 surge was ripping through New York City. Olive, a NYC-based artist, had just moved into a new apartment in Brooklyn. Despite their wealth of connections in the city’s art world, they felt a lack. They were bored. And like so many of us, they started scrolling.

I was in love. It was the feeling of being in love. I hadn’t spoken to anyone intimately. It was the pandemic. My brain was on fire.

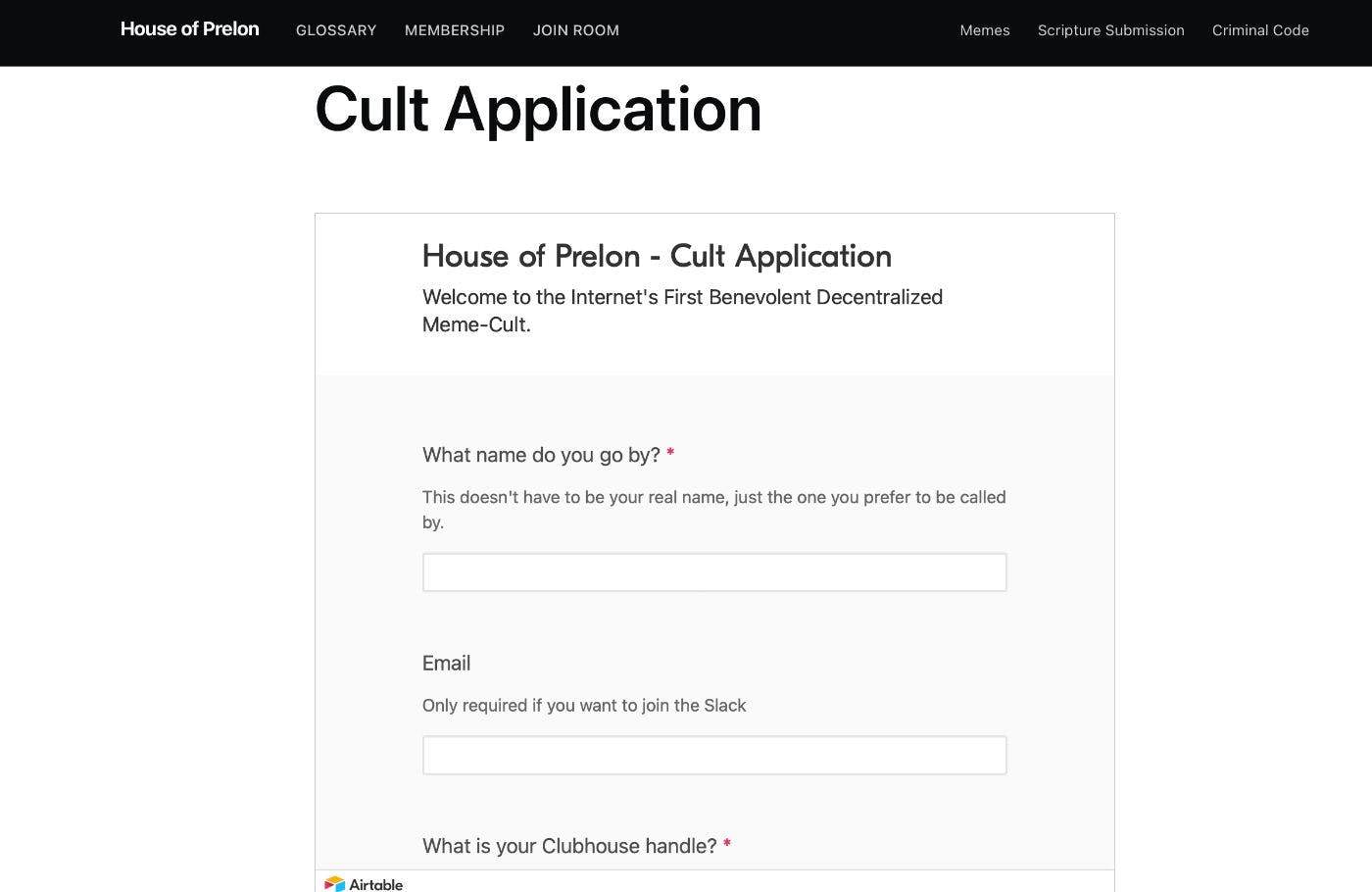

Olive was attending an event on Clubhouse, an invite-only internet space popular for its long-form voice chats. Olive was frequenting science and policy voice chats hosted on the platform. As one event wrapped up, an unruly attendee shouted, “Clubhouse was better before Elon!” The platform suddenly resounded with shouts of “Prelon! Prelon!” In a space full of internet elites and self-billed intellectuals like Clubhouse, this wasn’t supposed to happen. But, as it goes with so much of internet culture today, people began organizing themselves ad hoc. A new chatroom was born. Those participating in this impromptu community donned profile pictures of Elon in garb resembling that of Jesus. A meme was born, too.

So what?

Love, if you ask Olive. The chatroom, named “House of Elon”, became a calm albeit absurd space. They loved everything about it. “Welcome, Olive” the profile pictures of each Prelon acolyte would soothingly call out when Olive entered the room. In a time of pandemic, the House of Elon was e-stability. Members talked about politics and current events. They posted obscure memes. Linking to other online spaces of interest was common. Olive recalls fondly that everyone took turns.

One response to a centralizing internet is the construction of fringe, elite spaces, and that’s exactly what’s happening across the internet today. And, if you go on the House of Elon’s website, you can even join… via a “Cult Application.” A meme was iterated.

As memes iterate and circulate through chatrooms on the internet, so do users. Olive met another user, Charlie, in a Discord chatroom (a “server”) called Wet Brain Podcast. It had come highly recommended by fellow Prelon prelates. “Hey, I’m doing an NFT project,” Olive recalls Charlie messaging the server. Olive recalled,

I’m thinking, whatever… we’re all artists, and I didn’t know really know what an NFT was… and $300? I couldn’t fathom it.

That quickly changed.

To some, Charlotte “Charlie” Fang is a cult leader.

Lots of people from the New York art scene were on the Wet Brain Podcast server. Certainly, some, like Olive, had made their way there from the Prelon chatroom on Discord, but they came trickling in from chatrooms and social platforms across the internet. Many users were young and making art. All of them were looking for the next big thing. “There’s nothing avant-garde about the gallery scene in New York. 1980 to 2022, there’s no difference, no new language, the so-called avant-garde artists today are just using different images.”

So, with curiosity and extremely limited knowledge of what an NFT was, Olive clicked on Charlie’s link. They were blown away. This was what they had been looking for: something fresh, not rehashed collage work, not tired ideas. The NFT project was called Milady Maker, created by a secretive internet collective called Remilla. At first, Olive bought just one, spending about $300.

The NFTs were hugely unpopular and sales were stagnant. Olive, though, was hooked: on the ideas and art of these niche spaces, on going from niche to nicher internet space, on Charlie. They were electronically following Charlie’s work and those attracted to it, hopping from chatroom to chatroom, unbound by any social platform. What Olive saw from Charlie impressed them immensely. Charlie was building their art brand in niche sections of the internet. Charlie had been an early and influential member of SpiceDAO.

A Decentralized Autonomous Organization (DAO) is a kind of internet collective that uses cryptocurrencies to pool funds and make investments. The now-defunct DAO had purchased an illustrated manuscript of Dune at auction, having collected $3 million in crowdsourced funds, with plans to license its artwork and redistribute the proceeds. The art and hustle of Charlie elicited interest from starving artists like Olive who wanted something else out of art—and life generally. This electronic art was being circulated in multiple, niche yet global internet spaces, and all kinds of users, including many NYC-based artists, began to latch onto Milady Maker.

Around February 2022, things began to look up for Milady Maker, Charlie, and the Remilia Collective. Anonymous individuals associated with the Collective (some met pseudonymously online, some knew each other from the New York art scene) planned a so-called “Second Milady Rave” in the basement of Bella Ciao, a speakeasy in Manhattan’s Little Italy. As Olive tells it, the party was quickly scuttled by the police. Public records confirm that a party was broken up at Bella Ciao in early March 2022 for underage drinking. Regardless of the actual event, the spectacle of the Second Rave, as memorialized by memes, was pivotal for the NFT’s success.

What started (at least on its face) as a niche social media phenomenon was hot on NYC’s underground (and young) art scene. In the weeks that followed the Lower Manhattan bust, Milady Maker NFT owners used (i.e., posted, iterated) memes and used guerilla art tactics to advertise their NFTs and their community. The project quickly sold out, delivering about $3,000,000 in proceeds to Charlie and those associated with Remilia. Olive, who by now had purchased 6 Milady Maker NFTs for just under $2,000, saw the value of their collection grow to well over $10,000.

The “big story” Olive mentioned to me wasn’t about Remilia’s success. What Olive really wanted to tell me is that something had shaken the Milady world, including many in their “in real life” circles. Charlie, the pseudonymous internet figure at the head of Remilia, had just stepped down. There were tremendously concerning allegations being made against Charlie by other practitioners of network spirituality, a wide variety of accusations: like that Charlie had been pivotal in growing a white supremacist cult on the website 4Chan, and that accounts used by Charlie had groomed and abused young women drawn to their art. Charlie had even taken to Twitter and admitted to parts of it. Documents reviewed show disturbing, misogynistic, and abusive behavior by pseudonyms associated with and adjacent to Charlie. One image, a poster entitled “Sonya’s Rules”, is pink and features a picture of Hello Kitty; its content is highly misogynistic and seems meant for grooming young women.

A few days after my call with Olive, I received another call, from a number I didn’t recognize. Y, who remains anonymous, told me,

I heard you were writing a story about Milady. I was groomed.

Y, who lives in the United States, had been paid to moderate a chatroom and relay information about the people who found their way there. About their role, Y said,

My job was to talk to them, girls, entertain them, and report back with screenshots of the conversations I was having. Sonya would say, “Good job, Y, Good conversation.”

I asked Y what happened next:

I don’t know, and I didn’t care.

The identity of Sonya remains unclear and will likely remain so. Olive says it’s a pseudonym used by Charlie while others disagree and say Sonya was an early art collaborator with Charlie and their pre-Remilia collaborator, Sunny. One user, C, a blogger and internet artist, is concerned:

I genuinely believe a lot of the stuff is real and the ‘art project’ is a flimsy excuse that is doing a good job of tricking a ton of people.

When everyone is using pseudonyms, making niche and sometimes offensive art, and doing network spirituality, it’s hard to tell exactly what’s going on.

Charlie stepped down around the time Olive called me. They had admitted to Miya, a pseudonym associated with one of the “art projects” C referred to. Miya’s Twitter account has been suspended. I reviewed an archive of Miya’s tweets as part of reporting this story. They are chock full of racist and far-right ideas. Charlie, though, offered an explanation.

As I was writing this story, I received a notification of a Twitter Spaces, an impromptu and public voice chat—with Charlie in it. So, I jumped in, into a birthday party thrown for Charlie by the Remilia Collective, from which Charlie had stepped down a few weeks prior. Charlie explained Miya like this,

It was a project… [meant for the] acceleration of ideologies embedded in 4Chan and obscure hobby communities to absurdity, to the absurd limits. It combined Landian* acceleration, post-humanism theory fiction, and performative posting… Miya engaged in accelerationist philosophies… performative literature. I believe in cyber anarchism and free speech.

*Charlie was referring to the work of philosopher Nick Land. As described by Denis Chistyakov: “In general, accelerationists argue that technology, especially computer technology, and capitalism, in particular, its most aggressive, global variety, must be greatly accelerated and intensified, either because it is the best way forward for humanity or because there is no alternative. Followers of this trend in philosophy advocate automation, but are necessarily tied to the human factor. In the spirit of postmodernism (only with a call for a more accelerated implementation of its principles) they put forward ideas of a further fusion of the digital and the human. But they also stress that people must stop deluding themselves that economic and technological progress can be controlled” (https://doi.org/10.22363/2313-2302-2022-26-3-687-696).

Olive, who manages a New York City art gallery and is an artist in their own right, went from a bored pandemic night looking for good art to cyber anarchism.

To what extent had I, the researcher, become a meme?

In a way, I think related to this political moment’s “post truth,” in writing this essay I found it consistently difficult to distinguish fact from fiction. Did Charlie create a cult and groom young admirers? Or was “the cancel” of Charlie only a meme, and my research had become an iteration, I as the purveyor of a pseudo-empirical copypasta? How did Y get my number, and was their story legit? Who the heck is Charlie anyways? And does Olive honestly believe Charlie created a “tulpa” that was “born in their gut”? This confusion is consequent of the cyber anarchist approach to intervening against an internet these users loathe. Here’s what I think is going on.

In one light, people engaging in avant-garde e-art and absurdist “network spirituality” on Twitter are this generation’s cyberpunks. They are young, makers, and rejecting the status quo. Some of them are influenced by anarchist and libertarian ideologies. A few, drawn into the network spirituality practice, in reality, hold far-right ideologies and, when confronted with the products of ideological accelerationism as described by Charlie, don’t realize that they’re being made a fool. Many, many others are simply there for the art, or even more benignly, simply there to do something interesting and be a part of something, like make and share memes.

Those who philosophize on network spirituality see the electronic capitalist platforms of the internet as horrors, and their actions are intended to intervene. As Olive described,

There’s the Empire where everything is surveilled. It’s full of self-censoring, and it’s a dead space for creativity. Think Netflix or Facebook. Then there’s the Dark Forest. You can’t Google it. You have to find them, these vibrant, self-contained communities. There’s no ‘trade relationship’ with the Empire because the Empire’s surveillance is so potent and can corrupt the Dark Forest.

Recall that Olive found themselves in this space by jumping across platforms and spaces: from an elite, invite-only space on Clubhouse, to a reactionary and at first spontaneous (and then fastidiously curated) meme chatroom on Clubhouse, to a Discord room full of NYC and international artists, and finally to Twitter. The forms of posting (iterative, post-authorship, meme) and content of posting (often esoterica) permeate out through the Empire in a process that is enjoyable, creative, communal—and interferes with platform surveillance.

Surveillance algorithms are not programmed for absurdity.

Posting on the internet against surveillance can have ramifications beyond an intervention against surveillance in and of itself—it can be used to hide illegal activity. A few of the materials I reviewed were ostensibly this, but it’s hard to see. For instance, I was sent a website by Olive that looks, at first glance, like a professional homespun website with headlines like “Me” and “News.”

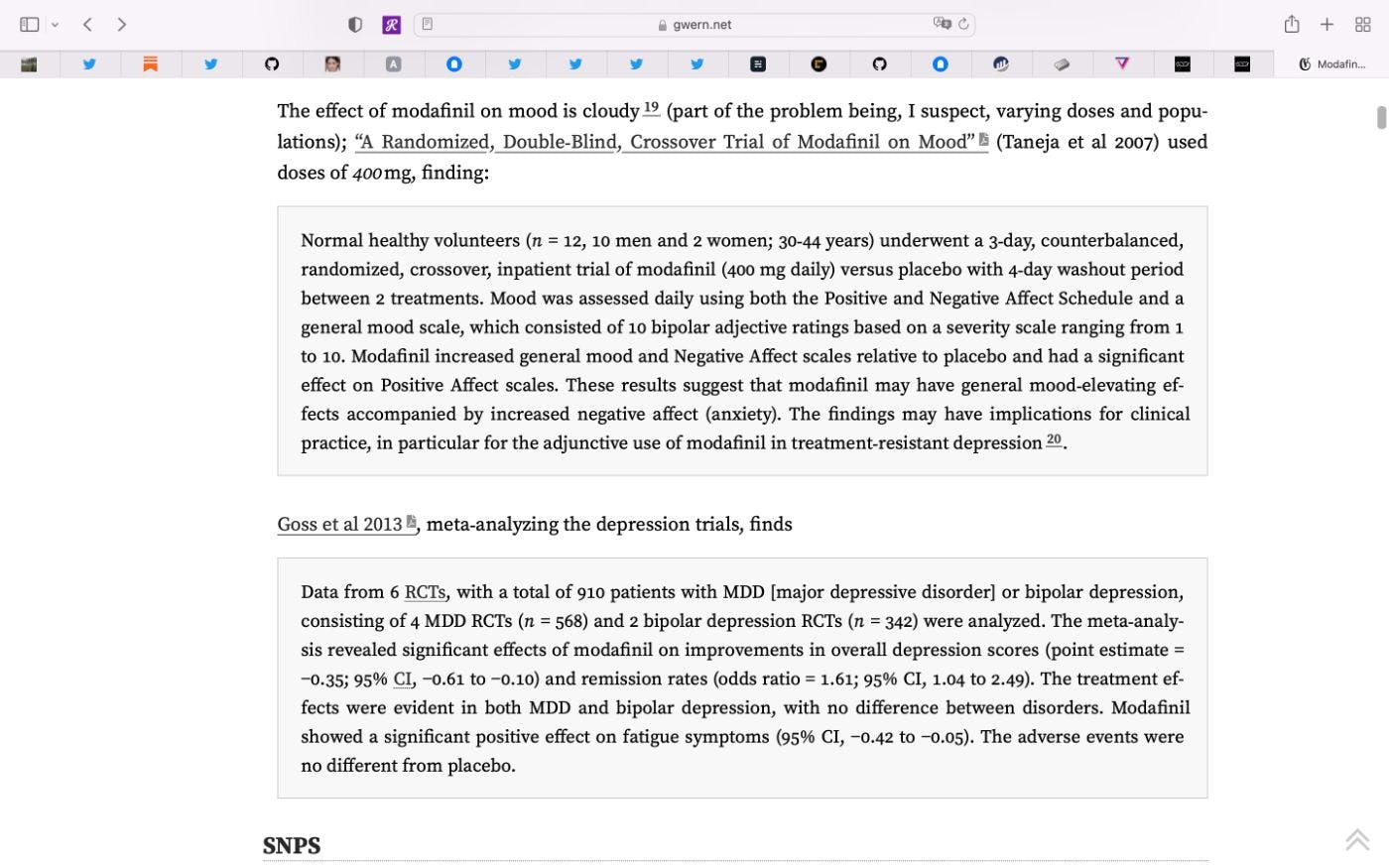

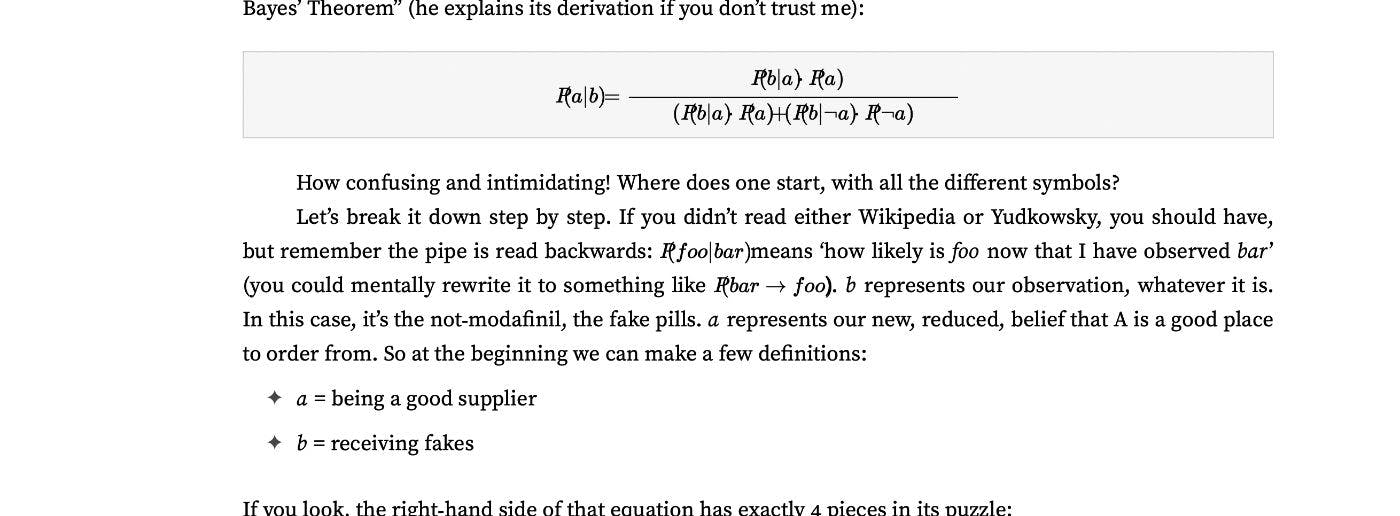

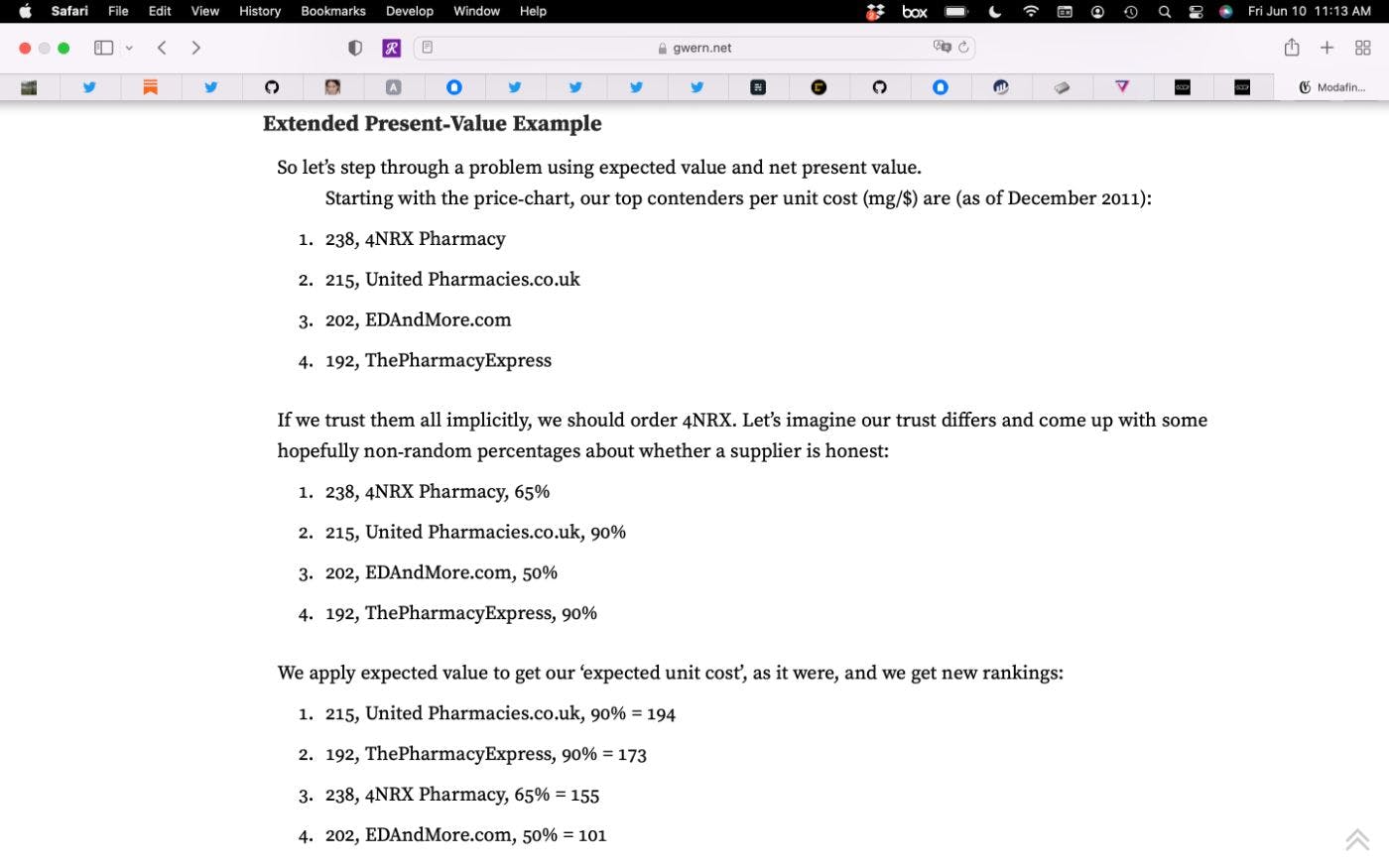

Searching around the website, I find a lot of things that are bizarre: an in-depth description of the website owner’s desk, methods by which their computer was created, and the age of their desk chair. On another page, I find an article that promises a “cost-benefit-informed perspective” for a pharmaceutical. It’s written like an academic article, with citations, charts, and formulas. But it’s utter bullshit, and while it’s art and perhaps doing the work of philosophical accelerationism in one sense, it’s meant to be a hidden-in-plain-sight linkage into the dark web, one section of the Hidden Forest Olive described. The academic lingo and presentation are meant to fool both algorithmic and human eyes into thinking this page is an academic article, as opposed to a linkage to suppliers of illicit drugs and the darknet markets that sell them.

Looks like an academic literature review.

If you scroll down, and down, and down some more, there’s silly formulas that don’t mean much.

Finally, we get to the websites where we can order modafinil, a controlled substance. The text is written to look like an academic analysis, but it’s nonsense. Out of the way of the prying e-eyes of surveillance and the uninitiated, for those who know where to look, it’s likely there’s a lot more here.

Did Charlie’s anti-surveillance radicalism create a shelter for others, like Sonya, who weren’t there to make a political statement but to exploit a weakness of platform governability, using the chaos and “performative literature” of internet spirituality as a cover? This type of writing against internet platforms obscures reality from both human and electronic eyes.

In terms of platform surveillance, algorithms aren’t equipped for the depth of meaning-laden meme images and memetic writing.* And when it comes to users, the problem of collectively governing an internet space is just as formidable. Most practitioners of internet spirituality I’ve spoken to in the year since the allegations of misconduct were first made state strongly that the grooming didn’t actually happen. I asked one user, “Are you sure you knew what was real and what wasn’t?” They responded that they in fact did since some of the most widespread allegations had been “copypasta,” a type of text-based meme.

My reply?

Have you considered that bad actors from within or outside of the community could subvert a meme for their own purposes? Isn’t that foundational to a meme in a way?

Other “avant” artistic projects talk about their use of iceberg theory and hypertext fiction as part of internet spirituality practices. The website linking to controlled substances (shown in the figures) appear to play the dual role of hypertext fiction and as a connection to illicit markets.

The amount of meaning that can be packed into one form through memetic processes is truly remarkable. The only other example that approaches this level of meaning-ladenness are religious sacramentals. These are cybernetic, or at the very least postmodern sacramentals.

Charlie, during his birthday party, stated forcefully that Remilia and network spiritualists “reject ugliness.” How can we know? During Charlie’s birthday party, which was attended by many NYC artists, some railed against “cancel culture.” Charlie said, “Cancel culture is a huge problem in art.” Unfortunately, what I think this thinking tends to enact in these spaces—and increasingly on the internet as a whole—is a rejection of accountability culture.

Charlie claimed that, “the internet itself is anarchist” and I can’t disagree more—the internet is programmed.

In real life, we have people, we have norms, and we have spaces. People can come together, co-construct a specific space, and establish norms for that space. We all know how to “program” a physical space because we’re social creatures in an embodied world. From my vantage point, the internet right now struggles to have anything but ephemeral cultures, spectacular shiftings with nihilistic and quick-moving undercurrents that make it challenging to conceptualize collective concerns and organize.

This is because we haven’t devolved the tools of building the internet into the hands of everyday users—we’re all either using big tech’s platforms or whatever’s at hand. Meanwhile, memes seem to have a tendency to move the real to the spectacular, and to talk about the real using the spectacular has ramifications.

Society at large can’t program our internet spaces. But it must if we’re going to live there.

Can network spirituality defeat the surveillance systems that are necessary for social media sites like Facebook and Twitter to work? As someone who studies platforms, I think the answer is yes, at least for the battle between today’s machine learning algorithms and today’s network spirituality absurdism.

After my conversation with Olive, I can’t help but think that so much of internet culture has taken on cult-like appearances. We share memes and GIFs to show our understanding of increasingly niche cultural knowledge. Spaces on social media platforms are as segmented as ever. The chatroom Y moderated was on an obscure platform most people have never heard of but is popular for its weak regulation (a fact, perhaps, unknown to many of those who wound up there.) As a society, we increasingly struggle to tell what’s real, and perhaps you’ve even found yourself saying, “Well, it doesn’t even matter.”

Meanwhile, our daily technologies are cybernetic, push notifications timed not to inform, but to make us act, to make us make someone else’s value, page refreshing not to connect with others but to see how many likes we’ve accumulated. The network spirituality of Milady Maker, whether an internet cult or not, is like so many other absurdist art movements in that its absurdity isn’t nonsense, it’s a critique. It is many other things, too, I believe.

Whether we can co-construct an internet that is socially governable, with rules made by its users that are knowable and able to be agreed upon (an e-social contract), seems an open and contested question. How policymakers who want to secure the internet but keep it free respond to this critique remains to be seen.

This article was originally published by Nicholas Croce on Hackernoon.